Billy Strings in Owensboro, KY on Sep 5, 2025: Tickets & Info

August 28, 2025

What Happens If You Walk Out of a Comedy Show? Etiquette & Consequences

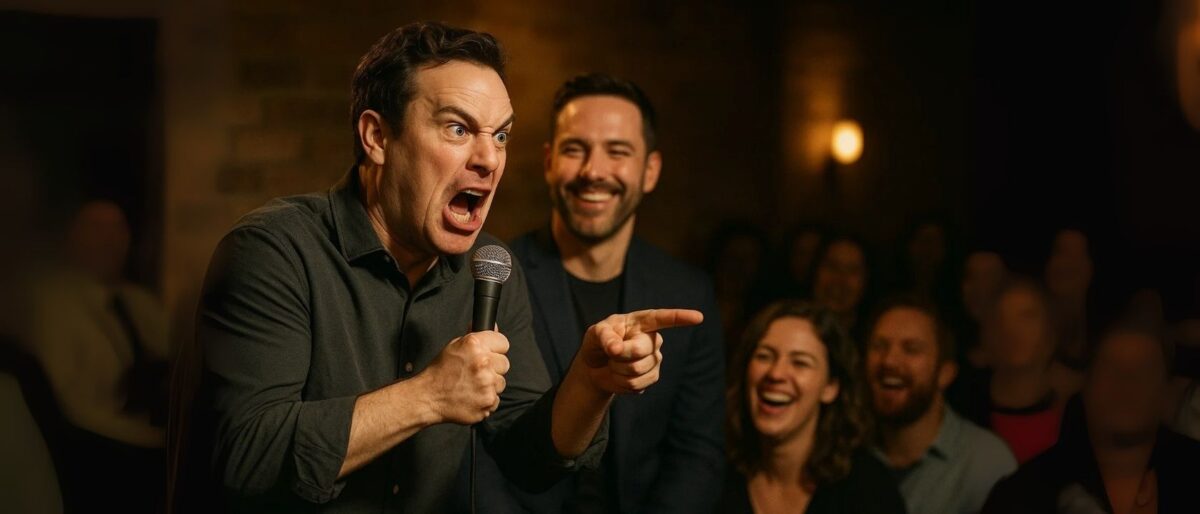

August 28, 2025What Is Roast Comedy? The Art of Insults and Laughter

Roast comedy is sharp, cheeky, and strangely affectionate. It’s where laughter lives in insults, and the target is often the one laughing the loudest. Mixing mockery with charm, roasts transform stings into smiles. But what makes this style thrive, and why do audiences crave the burn?

Definition of Roast Comedy

Roast comedy is a style of humor built on playful mockery. At its core, it’s about taking sharp jabs at someone in a way that entertains rather than wounds. The roastee—the person in the spotlight—is usually a celebrity, public figure, or friend who willingly steps into the hot seat. Instead of feeling attacked, they’re celebrated through exaggerated jokes that highlight quirks, flaws, and larger-than-life traits.

The ingredients of a roast are simple but powerful: over-the-top insults, clever exaggeration, and quick wit. A good roast never comes across as bitter; it balances on the fine edge between sting and laughter. The humor hits hardest when the audience knows it’s fueled by respect, not resentment. That wink of affection keeps the sharpest punchlines from crossing into cruelty.

For the audience, understanding intent is everything. They come expecting to laugh at insults precisely because they know they’re not meant to harm. In fact, the bigger the jab, the more obvious the underlying joke becomes. Roast comedy thrives on this paradox: the harsher the words, the warmer the atmosphere. It’s comedy that stings on the surface but lands as laughter at the core.

Origins and History

Roast comedy didn’t appear out of thin air—it grew out of the rowdy, irreverent traditions of vaudeville, burlesque, and early comedy clubs. Performers on those stages often poked fun at each other, tossing playful insults back and forth to keep audiences engaged. The humor was quick, brash, and full of exaggerated caricatures, setting the foundation for what would later become the roast format.

The practice became formalized in the mid-20th century with the Friars Club Roasts in New York City. These events gathered comedians and entertainers who would take turns skewering a guest of honor with brutal yet affectionate jokes. Though the material was biting, the atmosphere was celebratory. Being roasted meant you had “made it”—the insults were a badge of honor as much as a punchline. Legends like Don Rickles and Dean Martin cemented this culture, creating some of the most memorable roast moments in comedy history.

As television expanded, the Dean Martin Celebrity Roasts brought the tradition to mainstream America in the 1970s. Decades later, Comedy Central revived the format with edgier specials, featuring comics like Jeff Ross and Joan Rivers. These broadcasts turned roast comedy into a pop culture spectacle, drawing younger audiences who relished the mix of outrageous burns and celebrity vulnerability.

Today, roasts have shifted to match modern sensibilities. Social media fuels fast, viral “roast battles,” and comedians navigate a more sensitive cultural climate. The sharpness remains, but the targets and style evolve to keep pace with changing tastes. What started as barbed banter in smoky clubs has become a lasting genre of comedy, straddling tradition and trend.

Structure of a Roast

A roast may look chaotic on the surface, but it follows a familiar structure that gives the night its rhythm. At the center of it all is the Roastmaster, the host who sets the tone, introduces each speaker, and keeps the event moving. The Roastmaster often opens with their own jokes, warming up the crowd with quick burns aimed at both the roastee and the panel.

The panel is the next essential element. It usually consists of comedians, celebrities, or friends of the roastee who each take turns at the microphone. Their job is to deliver a mix of scripted and improvised jokes, roasting not only the guest of honor but sometimes each other as well. This back-and-forth builds momentum and creates an atmosphere where no one is safe, but everyone is in on the fun.

The spotlight, of course, is on the roastee—the subject of the night’s humor. They sit on stage, smiling, laughing, and occasionally cringing as the jokes fly. But the roast always closes with their chance to respond. This rebuttal lets them fire back, acknowledge the jabs, and usually end on a note of gratitude or affection.

The rhythm of a roast is consistent: setup, insult, laughter, repeat. Between the burns, there’s often an unexpected heartfelt moment, reminding everyone that beneath the insults is respect and admiration. This balance is what transforms a string of jokes into a roast—a ritual where sharp humor and genuine appreciation meet.

The Art of Insults

At the core of roast comedy lies the art of the insult, a craft that demands more than blunt delivery. The best roast jokes rely on exaggeration, hyperbole, and razor-sharp timing. A joke about someone’s quirks or habits becomes funnier when stretched to the extreme, landing as comedy instead of cruelty. Timing is equally critical—pause too long and the sting feels awkward, rush it and the punchline fizzles.

Not every insult hits the mark. The ones that land are clever, surprising, and clearly grounded in affection. They make both the audience and the roastee laugh. Flops, on the other hand, feel lazy, personal, or downright mean-spirited. Instead of sparking laughter, they leave an uncomfortable silence that breaks the flow of the roast. The difference isn’t always in the words but in the intention and delivery.

The secret is balance. A great roast joke has bite but never bites too hard. It playfully teases without tearing down, striking a balance between sharpness and warmth. That’s why most professional roasters “punch up” rather than “punch down.” Targeting someone powerful, famous, or well-loved makes the humor feel safe and inclusive, while attacking someone vulnerable risks crossing the line into cruelty. In roast comedy, the art of the insult is less about hurting feelings and more about creating laughter with a wink of respect.

Why People Love Roast Comedy

Roast comedy works because it taps into something people secretly enjoy—laughter at what’s normally off-limits. By poking fun at taboos, flaws, and quirks, a roast offers a cathartic release. The insults feel outrageous, yet safe, because everyone knows the target agreed to the spotlight. That agreement lets audiences laugh at things that might otherwise feel too sharp for casual conversation.

There’s also a powerful sense of community in the room. When a crowd bursts into laughter together, it creates the feeling of being “in on the joke.” The collective gasp followed by applause binds the audience to the roasters and the roastee. For a couple of hours, everyone shares in the same rhythm of setup, insult, and laughter.

Roasts also make celebrities more relatable. Hearing a movie star or athlete get ribbed for their odd habits or past flops reminds audiences that even icons are human. The jokes strip away polish and status, revealing quirks that people can laugh at without malice. That playful ridicule often makes stars feel warmer, not weaker.

Perhaps most surprisingly, roasts mix harshness with affection. Beneath every sharp jab lies respect, even admiration. It’s the paradox that keeps roast comedy from being cruelty: the harsher the burn, the more obvious the love behind it. Audiences walk away not just laughing, but often liking the roastee even more.

Risks and Controversies

Roast comedy thrives on edge, but that edge can cut too deep. When a roast crosses the line from playful exaggeration into outright cruelty, the laughter stops cold. What was meant as satire can quickly feel like bullying, and instead of uniting the audience, the joke creates tension or offense. This is the fine line every roaster has to respect.

Cultural shifts have made that line even more visible. In an era of cancel culture and heightened sensitivity, jokes that once drew laughs may now spark backlash. Audiences are more vocal about what feels acceptable, and comedians have to adapt. The standard for what counts as “funny” versus “harmful” is no longer fixed; it evolves with the times and the crowd in front of them.

Context, consent, and audience expectations are key. Roastees agree to be in the hot seat, and that consent signals to the audience that the insults are welcome. Without that understanding, a roast risks losing its playful foundation. Likewise, the makeup of the audience matters. A joke that kills at a Friars Club may fall flat—or spark outrage—on a broadcast to millions. In short, roasts succeed when everyone knows the rules of the game. When those rules are broken, the controversy often drowns out the comedy.

Famous Examples of Roast Comedy

Roast comedy has left a trail of iconic moments that shaped its reputation as both brutal and beloved. The tradition took root with the Friars Club Roasts, which began in the mid-20th century. These private gatherings in New York featured comedians and entertainers tearing into one another with ruthless jokes. What made them special was the mix of biting humor and genuine camaraderie—the tougher the insult, the deeper the affection beneath it. Don Rickles, often dubbed “the Merchant of Venom,” became a legend in this setting with his rapid-fire jabs.

In the 1970s, the format went public with the Dean Martin Celebrity Roasts. Broadcast on television, these roasts brought household names to the stage, from Frank Sinatra to Lucille Ball. Audiences at home got to see Hollywood icons roasted by their peers, and the events blended variety show polish with unfiltered wit. They became a staple of American comedy during that decade.

Fast forward to the 2000s, and Comedy Central Roasts reignited the format with a modern, edgier twist. Featuring stars like Charlie Sheen, Justin Bieber, and Pamela Anderson, these televised specials pushed boundaries with jokes sharper, cruder, and often more shocking. Comedians such as Jeff Ross, known as the “Roastmaster General,” and Joan Rivers, whose fearless wit made her unforgettable, carved their names into roast history through these performances.

Each era reflects its culture: the exclusivity of the Friars Club, the Hollywood glamor of Dean Martin’s specials, and the raw, edgy style of Comedy Central. Together, they prove roast comedy’s lasting appeal and its ability to adapt to changing tastes while keeping insult-driven laughter at the center.

Roast Comedy Beyond the Stage

While roast comedy is most famous on stage or television, its influence spills into everyday life. Friends often roast each other in casual conversation, trading lighthearted jabs that show closeness rather than hostility. A well-timed dig among buddies isn’t meant to cut—it signals comfort and familiarity. The laughter comes not from cruelty but from the shared understanding that everyone’s in on the fun.

Online culture has taken roasting to another level. Memes, comment threads, and playful “Twitter roasts” thrive on quick wit and exaggerated mockery. A viral roast can turn a simple picture into an internet sensation, where strangers pile on with creative burns. The digital setting amplifies the style, though it sometimes blurs the line between playful roasting and harsh trolling.

Roasting has even found a place in the workplace and social groups as team-building exercises. Organizing a roast for a boss retiring, a colleague’s birthday, or a sports team celebration brings people together. These events highlight quirks and inside jokes, strengthening bonds through shared laughter. They function as a release valve, diffusing tension with humor.

Still, there’s a difference between professional roast comedy and casual roasting. On stage, comedians spend hours refining material, balancing edge with timing. In personal settings, the tone is looser, less scripted, and often more forgiving. The same rules apply, though: the goal is to generate laughter without crossing into meanness. Whether at a comedy club or a family gathering, the spirit of roast comedy remains the same—tease with love, not malice.

How to Roast Like a Comedian

Roasting isn’t about throwing random insults—it’s about skill, precision, and knowing your target. The first rule is simple: know your subject well. The best jokes come from quirks, habits, or stories that feel authentic. If the audience recognizes the truth behind the exaggeration, the punchline lands harder.

The second rule is to keep it playful, not personal. A roast is about teasing with affection, not digging into wounds. Jokes about someone’s public persona, funny traits, or light flaws hit the right note. Personal attacks on sensitive issues, on the other hand, can shut down laughter fast. The line between funny and cruel is thinner than it looks.

Delivery matters just as much as the words themselves. A perfectly timed pause before the punchline or a sly smile after the insult makes all the difference. Comedians treat rhythm like music: setup, punch, reaction. Get the timing right, and even the harshest burn feels hilarious instead of heavy.

Finally, balance every barb with humor and a hint of respect. Even the sharpest jokes work best when wrapped in admiration. Audiences can sense when a roaster secretly likes their target, and that unspoken respect makes the burns easier to swallow. In short: roast with wit, roast with timing, and always roast with heart.

Conclusion

Roast comedy is more than a barrage of insults—it’s an art form that blends sharp wit with genuine affection. The sting is always softened by the smile that follows, reminding audiences that the goal is laughter, not malice. A roast done right leaves everyone, including the target, laughing together rather than apart.

At its best, roasting celebrates quirks, highlights humanity, and builds connections through humor. The balance of edge and warmth is what makes it endure across generations, from smoky clubs to streaming specials. If you’re curious, watch a classic roast to see masters at work—or try a light roast among friends, where the biggest burn comes wrapped in camaraderie. After all, in comedy, a little fire can spark a lot of joy.